The cutthroat trout is a fascinating fish. From tiny headwater streams to the Pacific Ocean, this adaptable salmonid is an icon of western North America.

This article delves into their intricate life cycle, diverse habitat preferences, and varied diets. Also covered are various subspecies like westslope, coastal, and Yellowstone cutthroat.

What is a Cutthroat Trout?

Cutthroat trout, scientifically known as Oncorhynchus clarkii, are a prominent member of the salmonid family found in western North America. They’re closely related to another popular fish, rainbow trout.

Cutthroat are renowned for their adaptability. Like most salmonids, they are opportunistic site feeders. They thrive in many cold, clean aquatic habitats like streams, larger rivers, lakes, and coastal ocean areas.

Cutthroat trout are iteroparous, meaning they can potentially spawn multiple times throughout their life.

“Discovering” Cutthroat Trout: Taxonomy and Naming

Cutthroat trout belong to the genus Oncorhynchus, which includes a variety of Pacific salmon and trout species. Their common names comes from the red slash on their throat.

Earliest European Encounter

The first known encounter of cutthroat trout by Europeans dates back to 1541. Spanish explorer Francisco de Coronado reported seeing trout in the Pecos River near Santa Fe, New Mexico. These trout were likely Rio Grande cutthroat trout, O. c. virginalis.

Cutthroat, Lewis, and Clark

Meriwether Lewis first observed cutthroat in 1805 near Great Falls, Montana. Lewis and co-leader William Clark described the fish, noting its similarity in form to other trout. Two features distinguished it: long, sharp teeth on the tongue and a notable red coloration on the ventral sides.

The cutthroat’s scientific name, Oncorhynchus clarkii, honors William Clark. Interestingly, the westslope cutthroat encountered in Great Falls on Lewis and Clark’s journey, is named for Lewis, O. c. lewisi.

Naming and Recognition of Cutthroat Trout

Its first scientific recognition and naming came in 1836 by Sir John Richardson, who referred to it as Clark’s salmon, Salmo clarkii. The specimens he based this on likely belonged to the coastal cutthroat trout subspecies.

The common name cutthroat trout was initially, but erroneously, associated with Salmo mykiss, or rainbow trout. This error was corrected with Richardson’s formal classification.

In 1989, both cutthroat and rainbow trout were reclassified under the genus Oncorhynchus. This move aligns them more closely with Pacific salmon than with Salmo species like brown trout and Atlantic salmon.

Evolutionary Origins of Cutthroat Trout

The evolutionary history of cutthroat trout is fascinating. Scientists suggest these fish evolved from a common ancestor in the Oncorhynchus genus. This ancestor likely migrated along the Pacific Coast into the mountainous regions of the western United States.

Among species in the genus Oncorhynchus, cutthroat are most closely related to rainbow trout. It’s believed they share a common ancestor. However, genetic similarities between the two species may be related to extensive introgression and hybridization.

Key cutthroat migration routes included the Columbia and Snake River basins. This migration is believed to have occurred 3 to 5 million years ago, during the late Pliocene or early Pleistocene epochs.

Subspecies of Cutthroat Trout

Cutthroat trout subspecies exhibit a rich diversity. Their differentiation stems from ancient migrations during the late Pliocene or early Pleistocene. Environmental shifts during these epochs isolated trout populations, leading to formations of distinct subspecies. Four primary evolutionary groups of cutthroat trout exist: coastal, westslope, Yellowstone, and Lahontan.

Coastal Cutthroat

Coastal Cutthroat Trout, O. c. clarkii, range from northern California to Alaska. The coastal cutthroat is considered the type species of cutthroat trout and includes the sea-run variant (SRC).

The Lake Crescent cutthroat trout, or silver trout, is sometimes classified as O. c. crescenti. This population in unique to Washington State’s Lake Crescent but isn’t considered a separate subspecies by many. However, this lucstine, piscovorous cutthroat has a silvery appearance and the largest recorded size of any coastal cutthroat: 12 pounds (5.4 kg).

Lahontan Cutthroat

There are several subspecies of cutthroat trout in the Great Basin. Among them, the Lahontan cutthroat trout, Oncorhynchus clarkii henshawi, is native to eastern California and western Nevada. The Lahontan cutthroat of Pyramid Lake attains the largest size of any cutthroat subspecies. It is currently ESA-listed as threatened.

Closely related to the Lahontan cutthroat trout is the Paiute cutthroat trout, O. c. seleniris. This Lahontan subspecies is endemic to only one tiny watershed in the eastern Sierra Nevadas of California. The Paiute cutthroat is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

The Humboldt cutthroat trout, O. c. humboldtensis, is found in Nevada and Oregon. It takes its name from the Humboldt River basin. The extinct Alvord cutthroat trout, O. c. alvordensis, once found in Oregon’s Alvord Lake tributaries, also falls under the Lahontan group.

Yellowstone Cutthroat Trout

In the Northern Rockies lives the most famous cutthroat trout subspecies, the Yellowstone cutthroat trout, O. c. bouvierii. It’s prevalent in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. Closely related to bouvierii is the Snake River fine-spotted cutthroat trout, O. c. behnkei, which is native to Idaho and Wyoming. The Bonneville cutthroat trout, O. c. utah, living in the Great Salt Lake tributaries, is another related subspecies.

Another cluster of related Yellowstone cutthroat includes the Rio Grande cutthroat, O. c. virginalis, and the Colorado River cutthroat, O. c. pleuriticus. The extinct yellowfin cutthroat trout, O. c. macdonaldi, was once found in the Twin Lakes of Colorado. A close relative is the greenback cutthroat trout, O. c. stomias, Colorado’s state fish. Once assumed to be extinct, a pocket of greenbacks were later found. Recovery efforts have brought them back from the brink.

Several subspecies from the Yellowstone cutthroat group were able to migrate over the Continental Divide into Atlantic drainages. This includes the Yellowstone, Rio Grande, yellowfin, and greenback cutthroat. It’s theorized that Two Ocean Pass, which links the Yellowstone and Snake River basins, is one of the pathways for this surprising migration.

Westslope Cutthroat Trout

The westslope cutthroat trout, O. c. lewisi, represents a unique branch within the cutthroat trout species. Similar to the coastal variant, westslopes have no closely related subspecies.

Before the introduction of nonnative trout and environmental changes, the westlope cutthroat was the most widely distributed and abundant subspecies of cutthroat trout.

Populations established east of the Continental Divide that drain into the Atlantic. Overall, the westslope cutthroat is native to parts of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, British Columbia, and Alberta.

Range of Cutthroat Trout

Cutthroat trout have the second-largest historic native range among North American salmonids after lake trout Salvelinus namaycush.

Native to western North America, cutthroat inhabit a range stretching from Alaska through British Columbia to northern California. Their habitats include the Pacific Northwest coast, the Cascade Range, the Great Basin, and the Rocky Mountains.

Reduced Ranges and Expansion

The range of certain subspecies, particularly the westslope cutthroat trout (O. c. lewisi), has dramatically decreased to less than 10% of their original habitat. This reduction is mainly due to habitat loss and the introduction of non-native salmonids like rainbow trout and other forms of cutthroat.

Introduction to Non-native Waters

Cutthroat trout have been introduced into non-native waters across western North America and distant locations like Arkansas, Maryland, Tennessee, and beyond.

Their dispersal isn’t as widespread as rainbow trout (O. mykiss). But notable instances include introduction into fishless lakes in Yellowstone National Park, Lake Michigan tributaries in the 1890s, and Lake Huron. In Arizona, cutthroat trout are regularly stocked in high mountain lakes in the White Mountains.

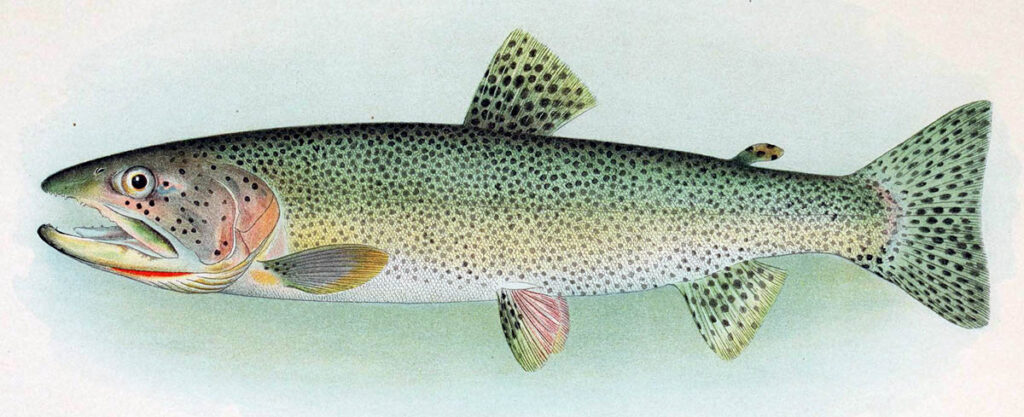

Cutthroat Trout: Coloration and Morphology

Cutthroat are a diverse fish that adapt their appearance to suit the local environment.

Distinctive Coloration and Markings

Cutthroat trout show varied coloration, reflecting their life stage and environment. Cutthroat trout show varied coloration. They are often on a spectrum between yellow, golden, or olive green. Rosy red gill plates are also common, and this color may extend down the lateral line, similar to rainbow trout. Some subspecies of cutthroat also have red or crimson bellies.

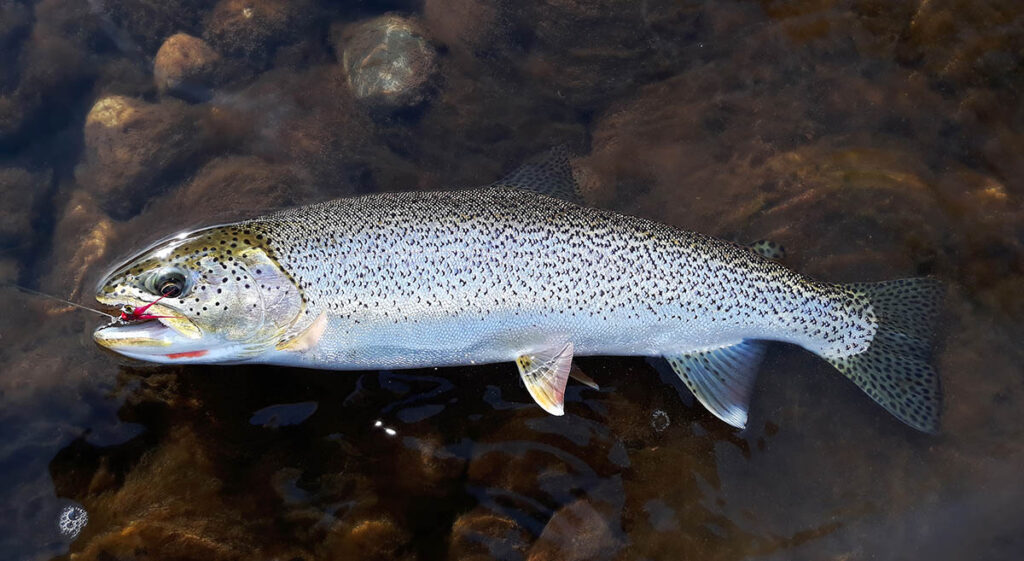

Sea-run and luctrine cutthroat tend to be brighter in coloration–sometimes silvery.

Most subspecies feature a prominent red or orange line under their mandibles. These marks led to their name “cutthroat.” This red slash appears after the fry stage. Notablly, some individuals might not display this mark. Adding to the confusion, some rainbow trout subspecies may also have this marking.

Younger cutthroat usually display large parr marks, similar to other salmonids. They also have numerous small dark spots on their bodies, especially above the lateral line and near the caudal peduncle. Some subspecies don’t have as many spots on their bellies.

Cutthroat trout also have spots on their dorsal, adipose, and tail fins. Spotting may also be present on their pectoral, pelvic, and anal fins, as well. Like many Pacific salmonids, cutthroat sometimes display white tips on their pelvic and anal fins. Their anal, pelvic, and pectoral fins are also often orange.

Morphological Features of Cutthroat and Differences Between Rainbow Trout

Cutthroat can look similar to rainbow trout in appearance. As fry, they’re essentially indistinguishable to the naked eye in many cases. And even as they mature, they can be difficult to distinguish.

Color and spotting aren’t reliable indicators for identification either. But in general, cutthroat often have larger spots than rainbow trout. One key morphological feature of cutthroat is basibranchial teeth at the tongue’s base. Rainbow trout do not have these teeth.

Another feature of cutthroat is that their maxillary extends beyond the eye’s back edge. However, some rainbow trout, especially larger, anadromous, and/or hybrid specimens, may also have a maxillary extending past the eye.

Changes in Appearance During Spawning Phase

Like most salmon and trout species, cutthroat often change in appearance close to spawning. But again, it’s worth noting that there can be considerable variation between individual fish and populations.

Cutthroat typically become darker and more vibrantly colored close to spawning. Many take on a deep orange coloration with red or pink bellies. This is especially true of males.

Sea-run cutthroat are a little different. They enter freshwater in the fall and typically hold until the following spring before spawning. Silvery at first, they gradually take on a yellowish-green color and rosy gill plates.

On occasion, larger sexually mature male cutthroat trout develop a small kype, which are extended jaws used for fighting other males. If they survive spawning, the kype will reabsorb back into their jaws.

Size and Weight of Cutthroat and Subspecies

Cutthroat trout vary significantly in size depending on several factors, including age, subspecies, habitat, and available food sources.

Age and Size

Age is the most obvious determiner of size, at least initially. Cutthroat fry are tiny and range from about 1.2 to 4 inches (30 to 100mm). Slightly older and larger cutthroat parr are still small, averaging around 5.9 inches (150mm).

How large cutthroat trout get is not primarily determined by age, however. Instead, it’s habitat and the available food that determines how large cutthroat can grow.

Cutthroat Size by Habitat and Subspecies

Small mountain streams tend to be deficient in nutrients, with fewer invertebrates to eat. Mature stream-resident cutthroat often max out at less than 12 inches (30.5 cm) in these environments. They also have shorter lifespans, as low as three or four years.

In larger rivers, cutthroat can migrate to find better feeding opportunities and may grow larger. In most rivers, a cutthroat trout over 3 pounds (1.4 kg) is considered a trophy fish. A maximum size fr fluvial cutthroat is around 6 pounds (2.7 kg).

Anadromous sea-run cutthroat, aka SRC, trout spend several months or more feeding in coastal waters. But despite the improved feeding opportunities, sea-run cutthroat rarely exceed 20 inches (50.8 cm) or 3 pounds (1.4 kg). The maximum size attained by SRC is around 6 pounds (2.7 kg).

The largest cutthroat trout tend to be adfluvial or lacustrine, aka lake dwellers. This mainly comes down to diet with smaller fish available as food. Coastal cutthroat in lakes can grow up to 30 inches (76.2 cm) or more. And the behemoths of the cutthroat world, Lahontan cutthroat, can grow even larger. The current IGFA world record cutthroat is a Pyramid Lake Lahontan that weighed 41 pounds (19 kg)!

Cutthroat Trout Habitat: Streams, Lakes, Saltwater, and Spawning

Cutthroat trout are fish that utilize almost every habitat available to them.

Cutthroat Freshwater Habitat

Cutthroat trout are cold-water fish that utilize a great variety of habitats. They primarily inhabit and spawn in cool, clear streams and rivers with gravel bottoms. They thrive in well-oxygenated waters without excess fine sediment. Lakes are also important habitats for some populations of cutthroat.

Cutthroat also use habitats that other salmonids may not. This includes swamps, ponds, off-channel habitats (ephemeral side channels, sloughs), and streams reaches well above anadromous barriers or steep gradients. Cutthroat can thrive in the tiniest headwater streams where other salmonids cannot.

Healthy riparian areas are critical to cutthroat in streams (and lakes). Established native vegetation reduces peak flows, erosion, and sedimentation – all of which can be detrimental to cutthroat redds.

Fallen trees (large woody debris) also create pools, accumulate spawning gravel, and provide protection from predators. Cutthroat density in streams is often correlated with the amount of available large woody debris.

Sea-Run Cutthroat Saltwater Habitat

Some coastal cutthroat trout migrate to the ocean after residing in freshwater. Sea-run cutthroat tend to favor near-shore waters. They often occupy very shallow water and prefer gravel and cobble beaches.

Sea-run cutthroat don’t spend much time in estuary habitat – usually less than a month. They also rarely make lengthy saltwater migrations. However, little is known about their behavior in the ocean.

Cutthroat Trout Spawning Habitat and Conditions

Cutthroat trout select specific habitats and conditions for spawning. A wide range of water temperatures are utilized for spawning, but typically fall between 43 to 57.2°F (6 to 14°C).

Cutthroat tend to choose gravel ranging from 0.5 to 3.0 inches (1.3 to 7.6 cm) in diameter. The ideal spawning sites have water depths between 8 and 9 inches (20 and 22 cm) near redds. Depths range from 4 to 12 inches (10 to 30 cm) in common spawning areas.

The general water velocity range of cutthroat trout redds is 10 to 24 inches per second (25 to 60 cm/s). They prefer sites with faster water downstream of the redd. This flow dynamic is often found around tailouts about riffles.

Cutthroat trout redds typically cover nearly 11 square feet (1 square meter). The pit within redds measures about 17 inches wide (43 cm) and 19 inches long (48 cm). It covers about half of the total redd area. Redd shape is designed to facilitate water movement. This helps with egg incubation. The shape aids in delivering oxygen and removing waste from the egg pocket.

Spawning cutthroat show territorial behavior. This behavior maintains space between redds. Redd superimposition is common, however. Later-arriving trout may build redds over existing ones. But this doesn’t often disrupt the egg pockets of previous fish.

On occasion, lacustrine cutthroat spawn in lakes. For this to happen, gravel with good water circulation is still necessary.

Life Cycle of Cutthroat Trout

The life cycle of cutthroat trout is extremely complex. Individual fish from the same population may exhibit a variety of life histories.

Cutthroat Trout Spawning

Cutthroat spawning occurs from late winter through the spring. Spawning can be as early as November in coastal rivers or as late as July in high-mountain lakes and streams.

Cutthroat trout are iteroparous, unlike their Pacific salmon relatives. This means they may survive spawning and can potentially do so several times.

Courtship, Redd Construction, and Egg Laying

Male cutthroat will court ripe females close to spawning. At the same time, males will battle for dominance and access to females.

The female cutthroat trout selects and excavates a redd in the stream gravel for laying eggs. Depending on her size, a female can lay between 200 and 4,400 eggs. An attending male fertilizes the eggs with milt (sperm).

After eggs the eggs are released and fertilized, female cutthroat will bury the egg pocket. Unlike Pacific salmon, cutthroat do not guard the nest. After spawning, they instead seek feeding opportunities. However, even though cutthroat are iteroparous, they don’t always survive the energetic demands of spawning.

Development of Eggs and Alevin

Eggs from older females tend to be more numerous and larger. This size difference plays a crucial role in the survival rate of the offspring. Larger eggs often lead to a higher chance of survival for the young fish.

After the eggs are laid and fertilized, they enter an incubation period. This period lasts for several weeks. The eggs hatch into alevins or sac fry in about a month. Alevin spend about two weeks in the gravel, absorbing their yolk sac before emerging.

Cutthroat Fry

Once the alevins have absorbed their yolk sacs, they emerge as fry. These young fish typically migrate to areas with low water velocity and off-channel waters. They stay in these areas throughout the summer and longer in some cases.

Once they emerge, cutthroat trout fry feed on zooplankton. They tend to utilize shallow habitats at the edges of streams to avoid predation from larger fish.

As they grow, cutthroat feed on progressively larger invertebrates.

Cutthroat Trout Parr

As cutthroat grow larger, their characteristic parr marks and red slash develop. Similar to other salmonids in freshwater, they also prefer deeper and faster water as they grow in size. This probably helps them avoid predation by mammals and birds.

In watersheds where cutthroat and rainbow trout cohabitate, cutthroat tend to favor deeper, slower-moving habitats like pools. However, in the presence of coho salmon, which also prefer deeper pools, cutthroat often occupy shallower riffles.

The diet of cutthroat trout parr gradually switches to larger aquatic organisms like insect larvae, amphipods, small fish, and fish eggs. Cutthroat will also opportunistically feed on terrestrial insects like grasshoppers when available. Overall, cutthroat are opportunistic feeders, just like their close cousins, the rainbow trout.

Lake-Resident Cutthroat Trout

Lake-resident cutthroat trout thrive in cool, moderately deep lakes. These lakes have shallows and vegetation, essential for food production. Unlike streams where food drifts toward cutthroat, lacustrine cutthroat cruise in search of food.

Lake-dwelling populations usually need access to gravel-bottomed streams for self-sustenance. Occasionally, they spawn on shallow gravel beds with good water circulation.

Life Cycle of Sea-Run Cutthroat – SRC

The early life cycle of sea-run cutthroat is the same as stream resident fish. Juvenile sea-runs typically spend between two and seven years in freshwater before migrating to the ocean, with three or four years being the most common.

SRC feed and grow in coastal waters and aren’t known to make lengthy migrations. Only a few months are spent in the salt before heading back to their natal estuary or stream. They often arrive in freshwater in the fall, where they overwinter until spawning the following spring.

Unlike their Pacific salmon cousins, sea-run cutthroat will eat during their freshwater spawning migration. Insects, small fish, salmon eggs, and carcasses are all on the menu for these opportunistic fish.

Diel Behavioral Shifts in Cutthroat

Like other species of salmonids, cutthroat trout are more active during the day during the summer months. During the winter, cutthroat tend to hide during the daytime and become more active at night. This is especially true when water temperatures are very cold.

How Long Cutthroat Trout Live and Age at Maturity

Juvenile cutthroat trout typically mature in three to five years after emergence, but there is a lot of variability.

The amount of food available to cutthroat and the speed at which they grow significantly impacts their lifespan and maturity.

Stream residents in cold, headwater streams grow slowly and mature early. Many only live between three and five years.

Cutthroat with access to more food and longer growing seasons tend to mature later and live longer. Fluvial, adfluvial, lacustrine, and anadromous cutthroat often live between seven and ten years of age.

Cutthroat trout rarely live past ten years of age.

Cutthroat Trout Diet and Feeding Habits

Like most trout, cutthroat are opportunistic sight feeders with diverse diets. Their feeding habits change with habitat and size.

The diet of cutthroat trout varies with the season and size of the fish. Larger trout tend to eat more fish. Smaller trout focus on invertebrates.

Feeding in Freshwater

In freshwater, their diet includes insects and invertebrates. They eat zooplankton, mayflies, stoneflies, and caddisflies. Other foods are true flies, midges, leeches, snails, and amphipods. They also consume damselfly larvae, small crayfish, and various worms.

Terrestrial invertebrates like grasshoppers, crickets, ants, bees, and spiders are on the menu. Larger cutthroat feed on small fish. This includes shiners, kokanee, and other small salmonids. They also eat salmon eggs and flesh when available.

In streams and rivers, cutthroat often take up feeding territories with easy access to drifting organisms. In lakes, cutthroat must move to find food.

Feeding in Estuaries and Saltwater

In estuaries, cutthroat trout eat amphipods, isopods, shrimp, and small fishes. Threespine stickleback and Pacific sand lance are common prey. Estuarine diets are rich and diverse and reflect the high productivity of these habitats.

In coastal waters, their diet includes larger prey. They eat small forage fish like anchovies and sardines. They also consume crustaceans and other invertebrates.

Predators of Cutthroat Trout

Cutthroat trout utilize a variety of habitats and life histories across western North America. Because of this, they have an equally diverse array of predators.

Freshwater Predators of Cutthroat Trout

Cutthroat trout face numerous predators in freshwater environments. They are opportunistic predators and exhibit cannibalistic tendencies, occasionally preying on smaller cutthroat. In regions where they cohabit, bull trout and pikeminnow readily consume cutthroat trout. Additionally, mature rainbow trout will prey on cutthroat trout.

This predatory behavior is also observed in introduced salmonids like lake trout and brook trout, which pose a significant threat to cutthroat populations.

A diverse array of sculpin species also target cutthroat trout small enough to fit in their mouths.

Birds are particularly adept at preying on cutthroat. This includes various species of ducks, gulls, kingfishers, terns, American dippers, eagles, and osprey. Most of these avian predators hunt cutthroat trout of younger age classes, including eggs, often capitalizing on their visibility in clear waters.

Mammals like otters and mink also play a role as opportunistic predators of cutthroat trout. Brown bears also prey on cutthroat in streams, most famously in Yellowstone National Park.

Saltwater Predators of Cutthroat Trout

In saltwater environments, the sea-run cutthroat trout variant faces a different set of predators. They become prey to larger salmon and trout. Various bird species, seals, and sea lions also target these sea-run cutthroats.

The presence of larger marine predators adds a layer of vulnerability for the sea-run cutthroat trout. For this reason, they often stick to very shallow water habitats.

Hybridization

Hybridization between different subspecies of cutthroat and introduced rainbow trout can dilute the genetic diversity and fitness of native cutthroat trout populations.

Cutbows: Cutthroat and Rainbow Trout Hybrids

Hybridization between cutthroat trout and introduced rainbow trout is a significant ecological concern. This process, known as introgressive hybridization, involves mixing genes from native and non-native species. It leads to genetic dilution and potential loss of unique evolutionary lineages of native trout.

Hybrid swarms, where a population consists solely of introgressed individuals, are rare. Typically, populations remain predominantly pure cutthroat trout.

Geography significantly influences hybridization. In areas where cutthroat and rainbow trout naturally overlap, pre-existing reproductive barriers reduce hybridization. These include differences in spawning times and life histories. Upstream areas in watersheds often show lower levels of introgression than downstream areas. This gradient suggests environmental factors and stream geography play crucial roles.

Effective management strategies focus on reducing non-native trout presence, especially downstream of natural migration barriers. Protecting upstream habitats, which serve as refuges for pure cutthroat populations, is also vital.

The Mysterious, Beloved Cutthroat

The cutthroat trout holds a revered status in western North America. This is evidenced by the fact that the cutthroat, and several subspecies, are the state fish of Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah.

Its adaptability across diverse habitats and opportunistic diet highlights its resilience. However, it faces significant threats, as well. This includes predation from introduced species like lake trout, genetic dilution through crossbreeding with rainbow trout, destructive land use practices, water diversion, and the impacts of climate change.

Understanding the unique life cycle of the cutthroat trout is essential for effective stewardship, ensuring its continued existence in our waterways.