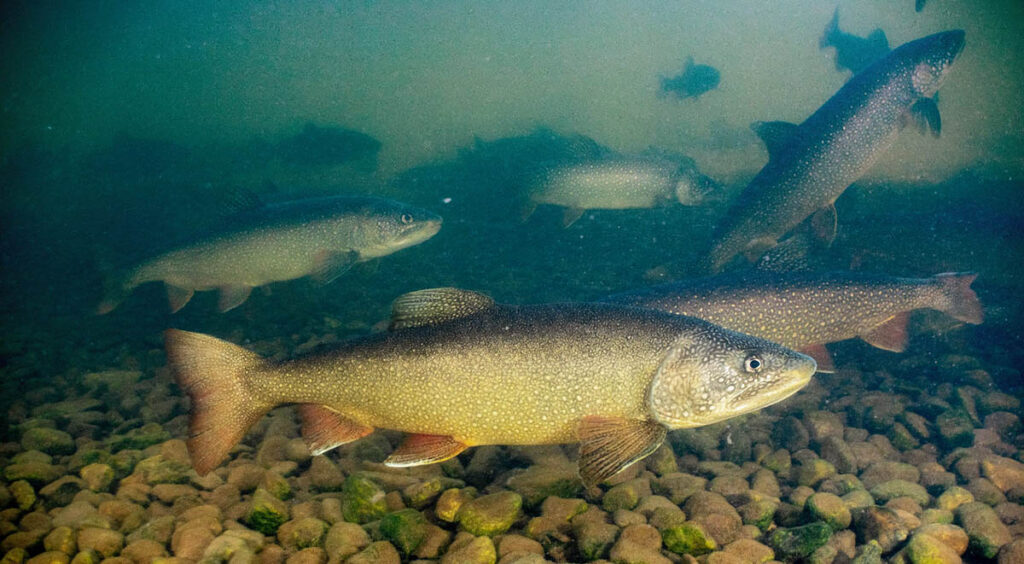

The lake trout are the kings of the north. They’re the largest species of char, the most widely distributed North American salmonid, and an apex predator. These fish-eating titans also behave quite differently than their trout and char cousins.

This article explores the deep-water world of lake trout. Learn about their life cycle, habitat, diet, subspecies, and more.

What is a Lake Trout?

Lake trout (Salvelinus namaycush) are a species of char that inhabit northern North America. Their range stretches across watersheds connected to the Atlantic, Arctic, and Pacific Oceans. Their territory includes the Great Lakes, the US Northeast, most of Canada, and much of Alaska. They are primarily lacustrine, spawning in lakes without building redds. Often associated with deep, cold lakes, lake trout also inhabit shallower and smaller bodies of water in the northern part of their range. There are also a few populations that utilize rivers (adfluvial and fluvial) and brackish (anadromous) environments.

Common names for lake trout include mackinaw, laker, lake charr, Great Lakes trout, togue in New England, and touladi in Quebec*. In a few waterbodies, lake trout have distinct morphotypes, including lean (common lake trout), siscowet, humper, and redfin in Lake Superior. Each of these morphotypes adapted to specific habitats and feeding strategies.

Mackinaw are the largest char and are primarily piscivorous. However, they also consume invertebrates like aquatic insects and opossum shrimp. Similar to other members of Salvelinus, lake trout are iteroparous, meaning they can spawn multiple times throughout their lifespan.

*On this page, the common names mackinaw, lake trout, laker, lake char, and lake charr are used interchangeably to refer to the same fish.

Taxonomy and Species

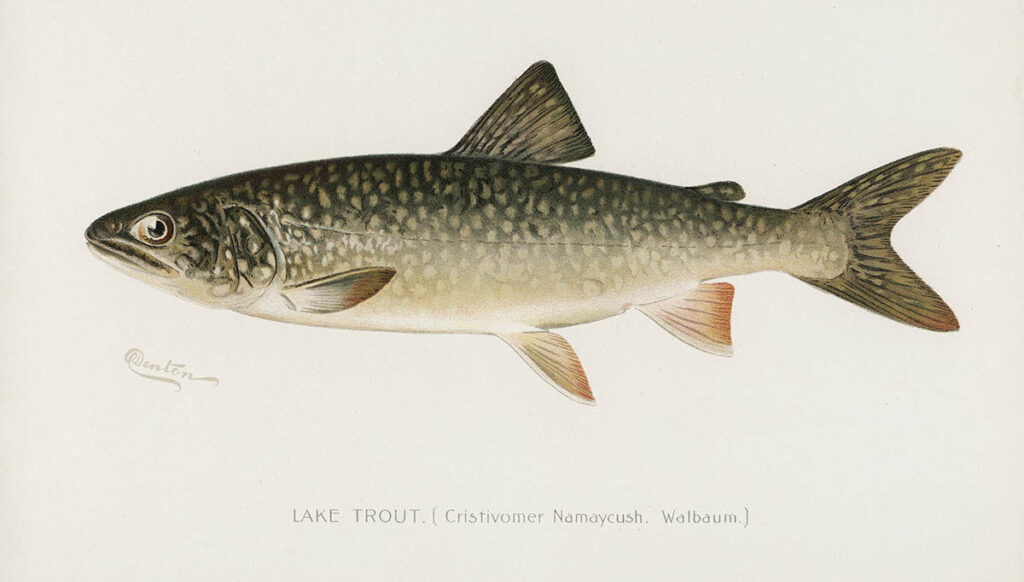

The lake trout’s scientific name is Salvelinus namaycush. It was first described as Salmo namaycush by Johann Julius Walbaum in 1792. Later, it was reclassified into the char genus Salvelinus, which also includes species such as brook trout (S. fontinalis), bull trout (S. confluentus), Dolly Varden (S. malma), and Arctic char (S. alpinus).

Lake trout are the sole species within the subgenus Cristivomer. They likely diverged from other char due to Pleistocene glaciation.

The name namaycush comes from the Cree word namekos, meaning “dweller in the deep,” reflecting the lake trout’s preference for deep lakes in many parts of its range.

Types of Mackinaw – Life Histories

Lake trout exhibit several distinct life history strategies depending on their environment.

Lacustrine lake trout are the most common life history type. They inhabit cold and oxygen-rich lakes and ponds. Lacustrine fish spend their entire lives within lakes, where they feed, mature, and spawn. Spawning occurs over rocky shoals at night. The vast majority of lake trout populations across North America have this life history, including the well-known lean and siscowet morphs.

Adfluvial lake trout live in lakes but migrate to tributary streams to spawn. This life history strategy is rare and occurs in specific populations where suitable spawning habitat exists in nearby rivers. These trout may spend most of their lives in lakes but migrate to river systems to spawn.

Fluvial lake trout are also rare. They reside primarily in large, lake-like rivers rather than lakes. These populations are highly localized and mostly in the northern parts of the lake trout’s range.

Anadromous lake trout are uncommon and most often found in Alaska and the Canadian Arctic. These fish migrate to coastal brackish waters during summer months to feed, returning to freshwater to spawn.

Lake Trout Subspecies and Morphotypes

The common lake trout (S. n. namaycush) is the most widespread form of lake trout. It’s sometimes referred to as the “lean” morphotype. They inhabit shallow to mid-depth waters in most lakes within their range. Common lake char are slimmer than other morphotypes and primarily feed on fish and invertebrates in the water column.

The siscowet (S. n. siscowet) is a deep-water morphotype found primarily in Lake Superior. Known for its high-fat content, this morph is adapted to survive in cold, deep environments. Siscowet trout are fatter and more buoyant than their lean counterparts, allowing them to thrive in depths exceeding 100 meters.

The humper is a small, deep-water lake trout morphotype that inhabits offshore shoals, particularly around Isle Royale in Lake Superior. Humpers are characterized by their compressed bodies, small heads, and shorter lifespans. They primarily feed on benthic prey, such as sculpin and invertebrates.

Redfin lake trout are one of the least studied morphotypes. They’re found in mid-depth offshore areas of Lake Superior. They are known for their reddish fins, especially during spawning, and have a more piscivorous diet compared to humpers. Redfin trout display larger eyes, indicative of their deeper-water habitat.

The Rush Lake trout (S. n. huronicus) is a dwarf subspecies that was once thought to be extinct. It only inhabits one lake in northern Michigan. This deep-water char is a benthic feeder and is about a quarter the size of a typical lean morph. Besides being smaller than lean lake trout, huronicus has a broad, blunt head and large fins. Rush and lean lake trout are segregated in the lake by utilizing different feeding niches, habitat preferences, and spawning locations and timing. Rush lake trout spawn in the mid to late summer at around 120 ft (37 m) deep.

Physical Characteristics, Identification, and Size

Mackinaw are the largest char species and relatively easy to identify.

Mackinaw Appearance

Lake trout have an elongated body with a streamlined shape, similar to other salmonids. Their coloration is typically less vibrant than other char, often displaying a range of shades from dark gray to olive on their dorsal side, transitioning to a lighter silvery or white belly. Their bodies are covered with large pale gray or whitish spots that contrast against their darker background, but they lack the red spots seen in other char species like brook trout. Unlike other species of char, lake trout don’t undergo dramatic color changes during spawning season.

A distinctive feature of lake trout is their deeply forked tail, which sets them apart from many other salmonids. This adaptation allows lakers to cruise through their pelagic environment. Their dorsal, pelvic, and anal fins often have a slight orange hue, and the ventral fins feature the classic char trait: a white leading edge.

Lake trout also have a large head with large jaws. Their maxillary (upper jaw) extends past the eye, similar to other members of the Salvelinus genus. Their mouths are filled with sharp teeth, which are used to capture a wide variety of prey, including fish and invertebrates. Mackinaw also have well-developed branchial teeth.

The amount of pyloric caeca in lake trout is much higher than other char, ranging from 90-200. In comparison, brook trout typically have 25-50 and spake have approximately 60-85 pyloric caeca.

This species exhibits significant variation in appearance across its morphotypes, especially between the slimmer, shallower-dwelling leans and the fatter, deep-water siscowets, with the latter having a bulkier build due to their high-fat content.

Sexual Dimorphism and Identifying Male and Female Lake Trout

Mackinaw exhibit minimal sexual dimorphism, meaning males and females look similar in size and morphology. The main visual difference is that males may have a slightly longer and more pointed snout than females, though this distinction is subtle. Unlike other salmonids, male lake trout do not develop kypes (hooked jaws) during spawning, as they don’t engage in competitive displays. Their body coloration remains similar between the sexes, even during the breeding season. As a result, visually identifying male and female lake trout outside of observing their behavior during spawning is nearly impossible.

Behaviorally, females are more active in nest selection and egg-laying during spawning.

Lake Trout Size

Lake trout sizes vary significantly depending on habitat and diet. In smaller lakes and colder waters, they tend to grow slower, with typical sizes ranging from 12 to 24 inches (30 to 61 cm) and weighing between 1 to 5 pounds (0.45 to 2.3 kg).

In larger, deeper lakes with piscivorous populations, mackinaw can reach greater lengths and weights. Average adults in these environments measure around 20 to 30 inches (51 to 76 cm) and can weigh 10 to 20 pounds (4.5 to 9 kg).

The world record lake trout weighed 72 pounds (33 kg) and was 59 inches (150 cm) long. It was caught in Great Bear Lake, Canada. This isn’t the biggest laker ever recorded, however. The largest specimen ever recorded was captured in a commercial net in 1961 from Lake Athabasca, Saskatchewan. It weighed an astonishing 102 pounds (46.3 kg) and measured 49.5 inches (126 cm) long. This fish was estimated to be between 20 and 25 years of age. Its testes never fully developed, which is how it grew so large.

Lake Trout Range

Mackinaw are native to northern North America. They thrive in cold, oxygen-rich lakes across Canada, Alaska, and the northeastern United States. They are considered the most widely distributed native salmonid in North America, occupying lakes as far west as Alberta and as far east as Nova Scotia.

Native Mackinaw Range

Lake charr inhabit the Great Lakes, Hudson Bay basin, and much of Canada’s inland lakes. Their native range extends throughout the northeastern United States, including Maine, New York, and Vermont. There are isolated populations of native lake trout in Montana, as well. They are also found in large lakes like Great Bear Lake and Great Slave Lake in the Canadian Arctic. In the southern parts of their range, they are restricted to deeper, cooler lakes.

Introductions

Lake trout have been widely introduced to lakes outside their native range. Beginning in the late 19th century, they were stocked in lakes throughout the western United States, including in states like Wyoming, Idaho, and Washington.

Outside of North America, lake trout have been introduced into Europe, Asia, and South America, although some attempts were unsuccessful.

Lake Trout Life Cycle and Behavior

Mackinaw have complex life cycles that vary depending on their genetics, available habitat, and the local ecology. This section highlights many of their core characteristics and behaviors.

Lake Trout Habitat

Mackinaw require cold, well-oxygenated waters to survive. They typically favor temperatures between 4-10°C (39-50°F). In the south of their range, these conditions are best met in deep, oligotrophic lakes with limited nutrients. Most populations spend their time in deeper waters, particularly in the warmer months. They also utilize shallower waters when temperatures are low. Further north, lake trout can inhabit much smaller and shallower bodies of water like ponds. They prefer rocky substrates for spawning, typically in wave-swept areas.

While primarily lacustrine, some lake trout populations also reside in rivers and streams. In the north, they often forage in large rivers and can also be found in rivers migrating between two lakes. Some populations even spawn in rivers, though this is uncommon.

A few Alaskan and Arctic populations also have individuals that migrate to the ocean. These anadromous lake trout are usually older and larger when they first venture into marine waters. They use coastal, brackish habitats for foraging, particularly in the summer. This species isn’t as tolerant of saltwater as other char, however, and isn’t known to migrate beyond brackish environments.

Reproductive Cycle and Spawning Behavior

Mackinaw, like other char species, usually spawn in the fall, with peak spawning typically occurring between September and November. Depending on the local climate, hydrology, and morphotype, lake trout may spawn throughout the year. Not all individuals spawn every year.

Lake trout are unique in that they are typically nocturnal spawners. During periods of high water turbidity, they may also spawn during the day.

Spawning often happens over rocky, cobble-sized substrate with space in between where water flow helps keep the eggs oxygenated. Mackinaw predominantly spawn in lakes rather than streams, though river-spawning populations exist in the Great Lakes and northern Canada.

Lake trout spawn in groups. Unlike other species of char, lakers are not aggressive or territorial while spawning. Females don’t create redds either. Instead, they broadcast their eggs over rocky shoals. Multiple males often fertilize the eggs as they are released. These eggs settle into the crevices between rocks, where they are protected from predators and strong currents. The fertilized eggs incubate through the winter months, hatching in the spring. Once hatched, the larvae, or alevins, remain hidden in the rocky substrate, surviving on their yolk sacs until they emerge as fry.

Juvenile Lake Trout: Fry and Parr

Mackinaw emerge from their rocky spawning sites as small fry, typically in the spring. These newly hatched fry still may rely on their yolk sacs for nourishment during the first weeks of life. Even before the yolks are fully absorbed, the tiny fry actively forage on tiny invertebrates like zooplankton.

Lake trout fry often move from their relatively shallow spawning areas to deeper water within their first month after emergence. Fry have seven to twelve dark vertical parr marks that help them blend into their environment.

After about a year, the juvenile lake trout are often called parr. By late summer, these juveniles typically range from 2 to 4 inches (5.1 to 10.2 cm) long, depending on environmental factors like water temperature and food availability. Their diet consists mainly of zooplankton and small aquatic invertebrates.

Mature Lake Trout

As lake char mature, they follow their food wherever the water temperature and oxygen levels are favorable. This means they can be found in various areas like deep, open water, near the surface, or close to shore.

Lake trout are opportunistic predators and will prey on many organisms, depending on availability and size. Once large enough, they are primarily piscivorous, feeding on fish. They may also consume larger aquatic invertebrates like Mysis shrimp and insects.

In some populations, individual adult lake trout may venture into brackish environments looking for greater feeding opportunities. These individuals are usually larger and over 10 years old. In a given population, anadromous lake trout typically grow larger than the fish that remain in freshwater. They often make annual migrations to coastal waters in the summer.

How Long Do Lake Trout Live?

Mackinaw have a relatively long lifespan compared to many other fish species. In most populations, lakers reach sexual maturity in around 6 to 10 years, but in cold, northern lakes, they may not mature until they are 10 to 17 years old. In productive environments, lake char generally live up to 10 to 20 years. However, in cold, oligotrophic lakes with limited food sources, they can live significantly longer.

The oldest recorded lake trout reached an impressive 62 years old in a northern Canadian lake. Their long lifespan is closely linked to their slow growth rate and late sexual maturity, making them vulnerable to overfishing and environmental changes.

Lake Trout Diet

Like most salmonids, lake charr are opportunistic predators, and their diet changes with their size and habitat.

Juvenile lake trout, known as fry and parr, primarily consume zooplankton, small aquatic invertebrates, and other tiny organic matter as they grow. As they mature, their diet diversifies, incorporating small aquatic insects and crustaceans, including Mysis shrimp, which are common in many deep-water habitats.

Adult lake trout are predominantly piscivorous, meaning their diet is primarily made up of fish. Their large heads and jaws allow them to eat fish up to half their body length. They feed on species such as Coregonus spp. (cisco and bloater), sculpin, Arctic grayling, and various smaller fish. In some environments, they may also consume larger invertebrates, including crayfish. The diet of adult lake trout varies depending on their environment, and in northern lakes, they may include terrestrial insects and amphibians during seasonal availability.

Anadromous lake trout, found in northern parts of their range, feed on marine prey, including small fish and shrimp, during their time in coastal waters.

Lake Trout Predators

Mackinaw, particularly as adults, have very few natural predators. Juvenile lake trout are more vulnerable and may fall prey to larger fish, including other lake trout and brook trout. In lakes with diverse predator populations, they may also be consumed by smallmouth bass, walleye, yellow perch, and introduced species like alewives.

In rare cases where lake trout utilize river habitats, birds like ospreys, bald eagles, and herons can prey upon them, along with mammals such as otters.

However, the most significant threats to lake trout populations come from sea lampreys and human activities. Sea lampreys, an invasive species in the Great Lakes, have historically decimated laker populations through parasitic feeding. Humans, through commercial and recreational fishing, are also considered a major predator.

Hybridization

Hybridization in lake trout primarily involves two notable hybrids: splake and lake trout x Arctic char hybrids.

Lake Trout x Brook Trout: Splake and Brookinaw

Splake are a hybrid between female lake trout and male brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis). These hybrids are typically created in hatcheries and are used in stocking programs to boost recreational fishing opportunities. While naturally reproduced splake occur, they’re exceedingly rare due to distinct habitat requirements and spawning behavior.

A similar hybrid to splake is formed when male lake trout breed with female brook trout. Called brookinaw, these hybrids are significantly less common than splake because fewer of the eggs survive to hatch.

Lake Trout x Arctic Char: Larctic Char

Natural hybrids between lake char and Arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus) are rare but have been documented in the Canadian Arctic and likely exist in parts of Alaska, as well. These hybrids are usually found in isolated lakes where both species coexist. There’s some evidence that this hybrid is usually a pairing of female lake trout and male Arctic char.

They display intermediate characteristics from both parent species. Interestingly, what was once thought to be the 29 lb (13 kg) record Arctic char in Sweden was later identified as a lake trout x Arctic char hybrid. These large hybrids are popular in Sweden, where they are called ”kröding.”

Conservation and Challenges

Lake trout (Salvelinus namaycush) populations have faced several challenges over the past two centuries, primarily due to overfishing, invasive species, habitat degradation, and pollution.

Overfishing

Throughout the Great Lakes, populations were heavily depleted by commercial and recreational fisheries. By the mid-20th century, overharvest had severely reduced mackinaw numbers, especially in Lake Michigan, Lake Erie, and Lake Ontario, where populations were completely extirpated.

Lake trout are particularly vulnerable to overfishing due to their slow growth and late maturity.

Invasives: The Alewife, Sea Lamprey, and Salmonids

Numerous lake trout populations are threatened by introduced species, particularly the Great Lakes.

The construction of the Erie and Welland Canals allowed invasive fish to enter the Great Lakes. None have been as destructive to native fish as the sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus). Sea lampreys devastated lake trout populations by attaching to and feeding on their blood and tissues. Chemical treatments to control sea lamprey populations have been successful, resulting in the partial recovery of some lake trout populations.

Alewives (Alosa pseudoharengus) are another anadromous fish that has negatively impacted laker populations in the Great Lakes. They also gained access to the upper Great Lakes by man-made canals. Adult alewives are known to prey on lake trout when given the opportunity. Conversely, adult lake trout feed heavily on the invasive alewives. This seems like a benefit at first glance. Unfortunately, alewives contain thiaminase, a thiamine-destroying enzyme. The resulting thiamine deficiency is passed on to their young, who have a much higher mortality rate as a result.

Introduced species of salmon and trout have also impacted lake trout negatively. Chinook salmon, coho salmon, pink salmon, rainbow trout, and brown trout have all been successfully introduced into the Great Lakes. Hatchery programs contribute significantly to the size of these populations. These introduced salmonids prey on juvenile lakers and compete for the same food sources.

Invasive species, combined with overfishing, led to the near-total collapse of lake trout in Lake Michigan and Lake Ontario, and only remnant populations persisted in Lake Huron and Lake Superior.

Pollution and Habitat Degradation

Industrial and agricultural pollution played a major role in lake trout declines, especially in the Great Lakes. In Lake Ontario, industrial pollutants such as heavy metals and PCBs severely degraded water quality. This led to oxygen depletion and habitat loss, contributing to the extirpation of lake trout by the mid-1900s. Agricultural runoff, particularly from fertilizers, has also caused eutrophication in many water bodies, resulting in excessive algal growth that further reduces oxygen levels.

Degradation of riparian habitats has also contributed to mackinaw declines. Residential and agricultural land practices increased sediment loads in streams, which are transferred to lakes. Fine sediments simplify lacustrine habitat and cover spawning areas. Sedimentation also leads to higher stream temperatures and reduced oxygen levels, which affect the lakes they feed.

The removal of large woody debris and shoreline vegetation, combined with habitat modification like sea walls, further reduced ecological complexity, food, and habitat for lake trout.

Stocking Programs

To combat population declines, hatcheries were established to propagate and stock lake trout in their native waters. These stocking efforts have helped maintain fisheries and have been part of restoration programs to reintroduce lakers to areas where they were previously extirpated.

While stocking has had some success, restoring lake trout populations to their historical levels remains a significant conservation challenge due to ongoing ecological pressures.

The Laker: Larger than Life

Mackinaw are an enduring symbol of clean, cold lakes in Canada and the northern US. They’re an apex predator playing a vital role in maintaining the balance of aquatic ecosystems. Their diverse life histories, morphotypes, and ability to adapt to varied habitats make them a subject of great interest to scientists and anglers alike.

However, overfishing, invasive species, and pollution threaten their populations. Understanding lake trout biology, habitat needs, and conservation efforts is crucial to preserving this remarkable species for future generations to enjoy and study.

Sources

Behnke, R. J. (2002). Trout and Salmon of North America. The Free Press.

Quinn, T. P. (2018). The Behavior and Ecology of Pacific Salmon and Trout (2nd ed.). University of Washington Press.

Marcus, M. D., Hubert, W. A., & Anderson, S. H. (1984). Habitat suitability index model: Lake trout (exclusive to the Great Lakes). Fish and Wildlife Service.

Wagner, E. J., Arndt, R. E., Billman, E. J., Cavender, W., & Whiting, P. J. (2002). Survival, performance, and resistance to Myxobolus cerebralis infection of lake trout × brook trout hybrids. North American Journal of Fisheries Management, 22(3), 760–769.

Ji, Y. Q., Warthesen, J. J., & Adelman, I. R. (1998). Thiamine nutrition, synthesis, and retention in relation to lake trout reproduction in the Great Lakes. American Fisheries Society Symposium, 21, 99–111.

Krueger, C. C., Shepherd, W. C., & Muir, A. M. (2014). Predation by alewife on lake trout fry emerging from laboratory reefs: Estimation of fry survival and assessment of predation potential. Journal of Great Lakes Research, 40(2), 415–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jglr.2014.01.009

U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. (1973). History of Salmon in the Great Lakes, 1850–1970. Great Lakes Science Center.

Montana Chapter of the American Fisheries Society. (2005, June). Lake trout. Retrieved from https://units.fisheries.org/montana/science/species-of-concern/species-status/lake-trout/