The rainbow trout is an adaptable and remarkable fish renowned for its versatility. Some of its populations even migrate to the ocean, becoming the famed steelhead. Rainbow trout skilfully avoid predators while navigating through varied habitats and environmental conditions.

This article explores the multifaceted existence of rainbow trout and steelhead, delving into their life cycle, diet, habitats, size, and much more.

Overview of Rainbow Trout

Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) are close relatives of Pacific salmon that inhabit western North America and eastern Asia. They exhibit various life history forms, including resident, fluvial, adfluvial, and ocean-migrant (anadromous), known as steelhead.

Unlike their Pacific salmon relatives, rainbow trout are iteroparous. This means they can undergo multiple reproductive cycles throughout their lives.

Their adaptability and diversity in life strategies makes rainbow trout a fascinating and ecologically significant species.

Species and Name

The rainbow trout is scientifically named Oncorhynchus mykiss. Johann Walbaum classified it in 1792 using Siberian specimens. Mykiss originated from the local name mykizha.

In 1989, a taxonomic shift occurred. Rainbow, cutthroat, and other Pacific Basin trout and char moved from Salmo to Oncorhynchus. Onco is Latin for hooked, and rhynchus is Latin for beak, referring to the males’ hooked jaws during mating.

Previous species names now represent subspecies. The North American coastal rainbow is O. m. irideus, and the Columbia River redband is O. m. gairdneri.

Range and Abundance of Rainbow Trout

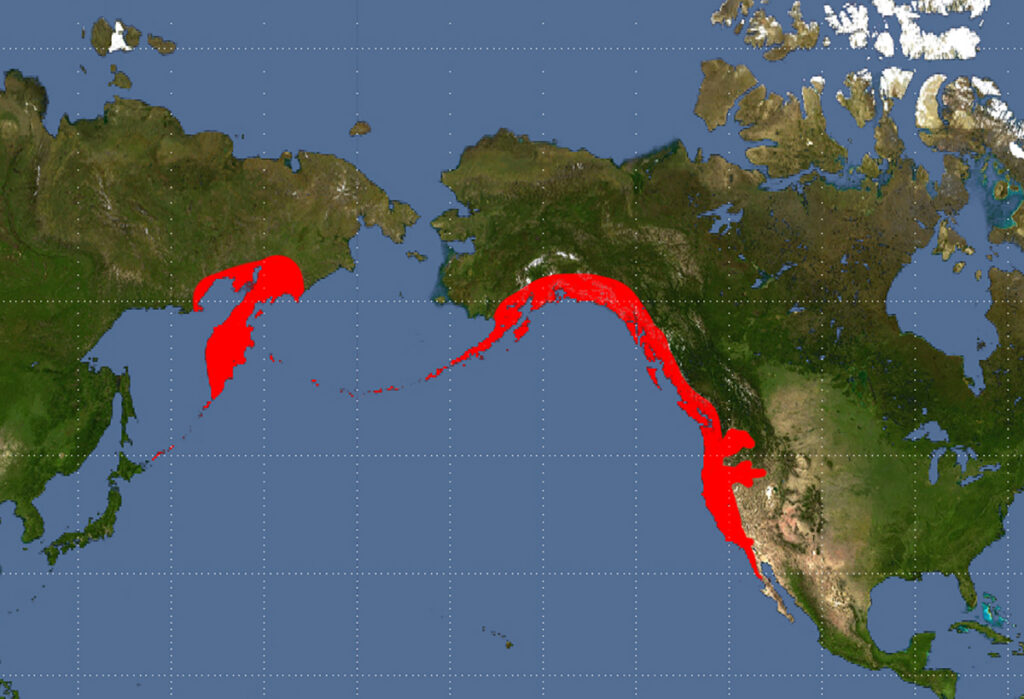

Rainbow trout are native to Pacific basin coastal rivers and their tributaries. Their range spans from Alaska to Mexico and extends west to Russia’s Kamchatka. Notably, Mexican forms of rainbow trout mark the southernmost boundary of any native trout or salmon species.

Introductions: Rainbow Trout from North Pacific to Global

The distribution of rainbow trout has expanded significantly since the late 1800s. People have introduced rainbow trout across most of the US and Canada. Rainbow trout and “steelhead” in the Great Lakes of the upper Midwest and Canada is the most famous example.

Many self-sustaining populations are now present around the world, as well. California steelhead transplanted to New Zealand have adapted well, though they are rarely anadromous. Argentina’s Río Santa Cruz is home to a large run of Atlantic steelhead. This cold water species has also been introduced in other parts of South America, Europe, Asia, and even in parts of Africa!

Angling and food production are the primary reasons for the spread of rainbow trout.

Abundance

In quality habitat conditions, resident, fluvial, and adfluvial forms of rainbow trout frequently exhibit significant abundance. This is not true of anadromous fish, however. Steelhead populations are typically smaller than Pacific salmon within a given watershed.

Rainbow Trout and Steelhead Size

Variability in rainbow trout size is influenced by genetics, environment, and life stages. Resident rainbows average 10-22 inches (25-56 cm) and 0.5-5 lbs (0.2-2.5 kg) but can grow larger in the right conditions. Within a given watershed, fluvial rainbows are often bigger than their more stationary resident forms.

Lake-dwelling and sea-going rainbow trout also tend to be larger than resident rainbows. Some fish exceed 30 lbs (13.6 kg) and 40 inches (101 cm).

The world record rainbow trout is a 48 lb (22 kg), 42-inch trout from Saskatchewan’s Lake Diefenbaker in 2009. This fish was a genetically-modified triploid, sparking controversy over the record.

The broad range of rainbow trout habitats, diets, and life history forms contribute to weight and length disparities.

Rainbow Trout Appearance

Rainbow trout display varied colorations influenced by age, environment, and subspecies. Generally, they exhibit a greenish back and black spots. A defining reddish stripe runs from the gills to the tail, more pronounced in breeding males.

Juvenile rainbow trout possess camouflage parr marks that may fade or persist into adulthood in some subspecies.

Steelhead smolts appear brighter with more subdued markings. Many open-water lake-dwellers and all subadult ocean-dwelling steelhead adopt a silvery hue, diminishing the prominence of the reddish stripe.

This adaptability in appearance facilitates their survival in disparate habitats.

The Rainbow Trout Life Cycle

Rainbow trout have one of the most complex life cycles of all salmonids. Almost all are born in gravel nests in freshwater streams. But after emergence from the gravel, rainbow trout exhibit a plethora of life histories.

Some rainbows will remain near their birthplace (resident), while others will migrate throughout the river basin (fluvial). Some rainbows grow and feed primarily in lakes (adfluvial). Still, others migrate to marine environments to feed (anadromous).

Regardless of their life history, rainbow trout return to their natal streams to reproduce. Unlike their Pacific salmon cousins, rainbow trout often survive after spawning, a characteristic called interoparity.

Let’s dive into more details about the complex life history of rainbow trout.

Early Life History: Rainbow Trout Eggs and Alevin

Rainbows start life as eggs (roe) buried in gravel in streams and rivers. There are places where rainbow trout spawn in lakes, but this is rare.

Nests (redds) of large rainbow trout like steelhead can contain thousands of eggs. Smaller resident trout will instead produce hundreds of eggs.

The rate of development inside the egg is directly related to water temperature, with warmer temperatures speeding up the process. Eggs hatch from less than a month to over three months after fertilization.

Rainbows hatch as alevin with large yolks attached. Once again, water temperature is an important variable. The warmer the water, the more rapid the growth of alevin rainbow trout. Once their yolks are mostly gone, they emerge as tiny fry.

Freshwater Residency of Juvenile Trout: Fry and Parr

Rainbow trout fry rear in their natal stream. They look for feeding territories near their birth site but eventually disperse. Rainbows spawned in lake outlets instinctively migrate upstream to the lake, while many others migrate downstream at night in search of better territories.

In general, rainbow trout fry hang out in the shallow margins of streams and lakes, where they feed on zooplankton. The shallows offer protection from predation from larger adult fish like cutthroat trout, bull trout, pikeminnow, and other rainbow trout.

As they grow, they compete for better feeding territories with other rainbow trout and salmonids in the stream. Their diet expands to include various aquatic and terrestrial invertebrates. The feeding habits of rainbow trout will be discussed in greater detail later in the article.

Juvenile rainbows tend to favor shallow and fast riffles. This is especially true when larger adult salmonids like coho salmon and bull trout are present in the stream.

Rainbow Trout Parr

The characteristic red stripe and parr marks of rainbow trout become more prominent as they grow. These rainbow “parr” are effectively camouflaged in the rocky, aerated stream environment by their markings.

Resident rainbow trout will remain in freshwater their entire lives, and some will remain close to their place of birth. Steelhead typically spend one to three years rearing in freshwater before migrating to the ocean as smolts.

Smoltification: Changes in Young Steelhead

Rainbow trout that migrate to the ocean, called steelhead, must transition from parr to smolts first. This prepares them for the radical environmental changes they will encounter.

The transformational process is called smoltification. The parr marks and color of rainbow trout begin to fade. Their backs become blue-green, their sides take on a silvery sheen, and their bellies become white and bright. This adaptation helps them blend into the marine environment better.

There are also significant internal changes happening to steelhead smolts. Changes in kidney and gill function enable them to handle a saltwater environment.

Environmental factors like water temperature and day length largely determine the timing of smoltification. For steelhead, this typically happens in the spring. When rainbow trout that will become steelhead don’t undergo smoltification in the spring, they remain in freshwater for at least one more year.

Steelhead smolts also experience changes in behavior. Primarily, they are motivated to travel downstream to the ocean.

Rainbow Trout in the Ocean: Steelhead

The ocean is a much more productive place than the freshwater streams and rivers that drain into the North Pacific. This is evidenced by the growth at sea for steelhead. A fish that spends two years at sea will undergo about 98% of its total growth in the marine environment.

Steelhead smolts typically migrate rapidly to the open ocean, spending little time in estuaries and coastal waters. They are now considered subadult steelhead.

The duration steelhead feed and grow in the North Pacific is highly variable. It depends a lot on the individual trout, plus the watershed they are from. Most steelhead spend one to three years at sea, though some stay longer.

“Half-pounder” steelhead from California and Oregon spend only a summer at sea before returning to their rivers immature that fall. They return to the ocean the following spring without spawning and continue to feed at sea. Eventually, half-pounders return to freshwater as mature adults to spawn.

It’s common for steelhead to make lengthy migrations. Fish from North America often travel as far east as Kamchatka. There are documented journeys as far as 3336 miles (5370 km)!

Return to Freshwater and Spawning

Close to sexual maturity, steelhead turn back towards their natal river. They can navigate the vast open Pacific due to their exceptional internal compass. As they get close, their sense of smell, sight, and memory lead them to the mouth of their birth stream.

Steelhead sometimes stray into other rivers and streams, but only rarely.

Changes in Appearance of Spawning Steelhead and Rainbow Trout

Steelhead that return to freshwater undergo a radical transformation. Their silvery color fades the longer they are in freshwater. Eventually, they revert to their “classic” appearance of olive backs, pink sides, and silvery bellies.

The jaws of some male rainbow trout become elongated, and males often develop a kype. Interestingly, when males survive their spawning season, their kype is reabsorbed.

Rainbow Trout and Steelhead Courtship and Reproduction

Male steelhead and rainbow trout fight for reproductive access to females, and females vie for the best spawning sites. Larger males usually get the best access to females, but they must successfully court them. Other satellite males on the periphery will also sneak in to fertilize released eggs.

Female rainbow trout may have several spawning events in a single season. Unlike salmon that typically dig a single redd, rainbow trout may dig several nests.

Male trout time the release of milt to fertilize the eggs. Spawning events are sometimes with the same males and sometimes not. After all eggs are released and buried, female rainbow trout don’t guard their nest like salmon. They instead seek feeding opportunities downstream.

Ideal Rainbow Trout Spawning Habitat

Spawning site selection in rainbow trout and steelhead is not random. Instead, site selection is determined by many factors that the trout innate understand.

Common variables in site selection include stream velocity, depth, and size of substrate (gravel, sand, etc). The larger the trout, the larger the substrate of the redd and the deeper the location. Steelhead utilize relatively large gravel for spawning, averaging around an inch in diameter. Smaller resident rainbow trout will use correspondingly smaller gravel for their redds.

Cool temperatures and ample dissolved oxygen are also important for incubating trout. The presence of upwellings or downwellings is also an important factor, depending on the watershed and its conditions.

Rainbow trout often spawn in the same high-quality locations year after year.

When do Rainbow Trout Spawn?

Rainbow trout generally spawn in the spring when the water begins to warm.

The exact timing of spawning depends primarily on the genetics of the rainbow trout in a given watershed. Selection favors optimal timing suited for the local environment and its conditions.

Other factors like water temperature and volume of flow also affect the timing of spawning.

Seasonal Runs of Steelhead

There are two primary types of anadromous rainbow trout: summer steelhead and winter steelhead.

Summer steelhead, or summer runs, enter freshwater well before spawning. Most arrive in freshwater in the summer or fall, but some fish arrive a full year before spawning.

Summer steelhead often travel higher into streams and rivers. In many rivers, they utilize habitat above natural barriers like waterfalls with impassible flows during winter and spring. Summer runs are also the dominant steelhead type in interior systems like the Columbia and Frasier Rivers.

Winter steelhead, or winter runs, spend much less time in freshwater than summer steelhead. They arrive at sexual maturity and spawn shortly after. Winter steelhead typically enter freshwater from early winter to spring and spawn from December to July.

The spawning migrations of winter steelhead are shorter than summer steelhead and take place closer to the ocean.

Diet and Feeding Behavior of Rainbow Trout and Steelhead

The diet of rainbow trout varies depending on its size, environment, and life history.

Egg Yolk and Opportunistic Feeding in the Nest

Like all salmonids, rainbow trout hatch under river gravel. These tiny alevin have attached yolks for nourishment. Even before completely consuming their yolk, alevin feed opportunistically. Once their yolk is gone, rainbow trout must fend for themselves.

Freshwater Rainbow Trout Diet

Rainbow trout fry feed primarily on zooplankton and floating organic material. As they grow, a wide spectrum of organisms are on the menu.

Aquatic insects make up a large proportion of the diet of freshwater rainbows. This includes larval and adult mayflies, caddis flies, stoneflies, and other types of insects. They also eat amphipods (scuds), crayfish, worms, snails, and terrestrial invertebrates.

Rainbow trout are highly opportunistic feeders. In some populations, large resident rainbow trout even feed on mice!

Rainbow trout in streams take feeding positions where they can intercept drifting organisms without much effort. In lakes, trout cruise in search of feeding opportunities.

When available, salmon and trout eggs are significant sources of nutrients for rainbow trout in streams. Even pieces of salmon carcass are fair game.

Steelhead Feeding in the Ocean

In the ocean, steelhead trout consume a variety of invertebrates, including shrimp, krill, and other amphipods, as well as squid. Their diet also consists of small fish species such as capelin, sand lance, herring, sardine, anchovy, and mackerel.

Do Steelhead Eat in Freshwater?

It’s believed that steelhead don’t feed during their freshwater spawning migration. But there is anecdotal evidence that some feeding may occur, especially with summer steelhead.

Respect for Rainbow Trout

With its adaptability and diversity of life histories, the rainbow trout is one of the world’s most fascinating fish. From the marine migrations of steelhead to mountain stream rainbows, this species can thrive in a broad array of environments.

Unfortunately, not all rainbow trout populations are doing well. This is especially true at the southern end of its range and for steelhead.

Today, rainbow trout face many challenges, both man-made and natural. As humans, we can be a force for good and help them. Awareness of the rainbow trout and its complex life cycle is the first step. Thank you for taking the time to learn a little about rainbow trout.