The Dolly Varden is a fish with a history of confusion and misidentification. Complex in nature and often mistaken for other char species, it’s a challenging subject for researchers.

This article attempts to break through some of the confusion, diving into the intricate world of the Dolly Varden. We’ll examine the species’ taxonomy and common names, describe its physical appearance and size, detail its life cycle, discuss conservation topics, and more.

What is a Dolly Varden?

The Dolly Varden (Salvelinus malma) is a char inhabiting the North Pacific and Arctic basins. This species, characterized by its vibrant coloration, got its name from a Charles Dickens character from the novel Barnaby Rudge, known for her bright dresses. The Dolly Varden is often confused with the related bull trout and Arctic char due to their similar appearances.

Dolly Varden, sometimes called Dollies, exhibit a range of life histories. This includes resident, lacustrine, and anadromous forms. They are also iteroparous, capable of breeding multiple times throughout their lives.

Dolly Varden are challenging to pin down taxonomically and can be classified as a single species with several subspecies or divided into multiple species and subspecies.

Salvelinus malma: Names and Taxonomy of Dolly Varden

Pinpointing one exact fish as a Dolly Varden (Salvelinus malma) is challenging due to its frequent confusion with similar species and the presence of several subspecies, which may warrant classification as distinct species. This complexity is compounded by its diverse life history traits and varied distribution.

The Name “Dolly Varden”

The name “Dolly Varden” originates from a colorful character in Charles Dickens’ 1841 novel Barnaby Rudge. Dolly Varden was known for wearing vividly colored dresses, which inspired similarly vibrant patterns of cloth named after her.

The name was applied in the 1870s to describe colorful and large “salmon-trout” in California’s McCloud River. The name stuck, and Dolly Varden became the common name in North America for Salvelinus malma. Interestingly, the original Dolly Varden wasn’t the species malma. It was the closely related bull trout (Salvelinus confluentus), which wasn’t classified as a distinct species until 1978.

Dolly Varden are often affectionately called Dollies. And many anglers, especially older generations, use the name Dollies to describe both bull trout and Dolly Varden.

Taxonomy and Subspecies of Dolly Varden

As mentioned previously, Dolly Varden have a complicated taxonomy. Overall, they can be divided into two forms: Northern Dolly Varden and Southern Dolly Varden. The ranges of these two types overlap, and it’s not always clear where one ends and the other begins.

Northern Dolly Varden: Salvelinus malma malma

Northern Dolly Varden (Salvelinus malma malma) are found around the Alaska Peninsula northward into the Arctic and throughout the Kamchatka Peninsula. The scientific name malma comes from the colloquial term for this fish in Kamchatka. Northern Dollies are typically anadromous, migrating from sea to spawn in freshwater.

This form of Dolly is distinguishable from the southern forms in several ways. They have fewer chromosomes (78 vs. 82), higher gill raker counts (20-24 vs. 16-19), and more vertebrae (66-70 vs. 62-65).

In one way, Northern Dolly Varden appear more closely related to Arctic Char (Salvelinus alpinus), which also has 78 chromosomes, than to the southern form of Dolly Varden! Past hybridization between Artic char and Northern Dollies may be one reason.

Southern Dolly Varden: Salvelinus malma lordi and krascheninnikovi

Southern Dolly Varden are often divided into North American and Asian forms.

North American Southern Dolly Varden (Salvelinus malma lordi) range from the Alaska Peninsula to the Puget Sound. This subspecies is closely related to bull trout (Salvelinus confluentus).

Asian Southern Dolly Varden (Salvelinus malma krascheninnikovi) are found from the Aleutian Islands extending to the Kuril Islands and south to Hokkaido. This form can be further classified into several distinct forms and is also sometimes classified as (Salvelinus curilus).

The scientific classification of the Dolly Varden continues to be a subject of study. Ongoing research may further refine these classifications based on genetic, ecological, and morphological data.

Are Dolly Varden Trout or Char?

Dolly Varden are often called trout, but is this accurate?

Technically, Dolly Varden are char – not trout. Dolly Varden belong to the Salvelinus genus. This group of fish includes Arctic char, bull trout, white-spotted char, lake trout, and brook trout.

The closest relatives of Salvelinus are the Pacific trout and salmon of the genus Oncorhynchus. They are more distant relatives of trout and salmon of the genus Salmo.

Dolly Varden Range

Dolly Varden are found across the North Pacific rim and parts of the Arctic Ocean. In North America, they range from the Puget Sound of Washington through coastal British Columbia, across Alaska, and to the Mackenzie River of the Northwest Territories. Dolly Varden are also present in Asia from Siberia to the waters of northern Japan and Korea.

Within this broad range, the Northern Dolly Varden occupy the northernmost areas, extending into the Arctic basins. Southern Dolly Varden, both North American and Asian, are distributed more southerly.

Dolly Varden Color and Morphology

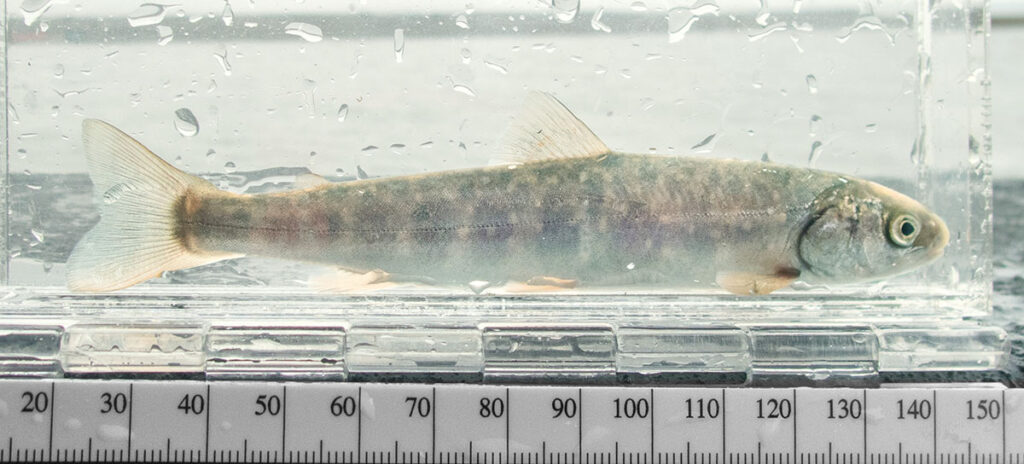

Juvenile Dolly Varden (fry and parr) are relatively muted in coloration. They have dark brown to gray bodies with cream-colored spots and bellies. Their fins are generally transparent with a light orange hue.

Mature Dolly Varden have striking, vivid colors typical of char species. In freshwater, their appearance includes small red to pink spots against a background ranging from emerald green to grayish blue.

Close to spawning season, they may display ventral colors from peach to crimson. Their ventral fins are also often vividly colored from orange to red with a white anterior edge. Their snouts may turn reddish-orange, as well.

During the spawning season, male Dolly Varden often develop a pronounced kype. If they survive spawning, their kype will shrink and reabsorb into their jaws.

In marine environments, their bodies and fins take on a silvery hue, which obscures their spotting. In the ocean, their bright appearance acts as camouflage.

Dolly Varden Size

Dolly Varden sizes vary significantly by life history type and location. Stream-resident individuals are typically smaller, averaging 4-5 inches (10-13 cm) and 1 ounce (28 g). Anadromous and lacustrine forms grow larger – usually measuring 14-18 inches (36-46 cm) and weighing 1-1.5 pounds (0.45-0.68 kg).

The Alaska state record Dolly is 27 pounds 6 ounces (12.4 kg) fish from Wulik River, and the IGFA all-tackle world record stands at 20 pounds 14 ounces (9.5 kg) from the same river. Besides the Wulik, the Kivalina and Noatak Rivers are recognized for harboring particularly large Dolly Varden.

The Varied Habitat of Dolly Varden

Dolly Varden inhabit diverse habitats across their range and are adaptable to both freshwater and marine environments. In freshwater, these fish favor deep runs and pools in streams and rivers. They typically spawn in the gravel-bottomed, high-gradient riffles during September and October. Shoreline cover and vegetation are important for safety and also provide food like terrestrial insects for juveniles.

In marine settings, Dolly Varden are found in nearshore waters, where they utilize the coastal areas as feeding grounds. Their ocean habitat is characterized by cold, nutrient-rich waters, which support a variety of prey items. Some populations of Dolly Varden travel through offshore waters during lengthy migrations to distant overwintering sites.

Anadromous Dolly Varden don’t remain in marine waters year-round. Instead, they overwinter in lakes or rivers outside their home drainage. Southern Dolly Varden tend to prefer lakes connected to rivers. Northern Dolly Varden often overwinter in rivers with springs or groundwater, ensuring a warm environment even in freezing temperatures. Groundwater sources are also favored for spawning site selection to ensure embryos aren’t too cold.

The Complex Life Cycle of Dolly Varden

The life cycle of Dolly Varden is like a complex ecological puzzle. These cold water-loving char have diverse life history strategies, including resident, lacustrine, and anadromous forms. These life histories vary not only among different populations but also between subspecies, adapting uniquely to their local environments.

A unique aspect of the Dolly Varden life cycle is the need for quality overwintering habitats. It’s essential for their survival and reproductive success across these varied life histories.

Spawning Dolly Varden: Season, Site Selection, and Behavior

Dolly Varden are fall spawners, with spawning usually occurring from September to October.

They exhibit high site fidelity, returning to their home streams to spawn. Dollies are also very selective in their spawning site. These areas are often in the upper or middle reaches of the watershed, with small to medium gravel sizes suitable for egg deposition and protection. Most redds (nests) are in less than three feet of water in areas with moderate current velocities and ample dissolved oxygen.

Northern Dolly Varden require sites with local groundwater inputs, which prevent embryo freezing and provide a favorable environment for newly hatched fry. Springs and groundwater seepage may also be an important component in site selection for Southern Dolly Varden, depending on the local environment.

The spawning behavior of Dolly Varden typically involves pairing of a dominant large male and female. Smaller males, often precocious parr, linger as satellites around the main pair. These satellite males attempt to fertilize eggs during spawning by sneaking closer to the pair. However, both the larger male and female actively defend their spawning territory, attacking satellite males who venture too close.

Frequency of Spawning and Repeat Spawners

The life history type of Dolly Varden also plays a role in the frequency of spawning events. Stream-resident fish often spawn annually. Their first spawning event is around three or four years of age when they are only 4-5 inches (10-12.7 cm) long.

Anadromous and lacustrine Dolly Varden often spawn in alternating years. Spawning is more energetically taxing on these larger fish, but they make up for the intermittent frequency with higher fecundity.

Dolly Varden are iteroparous, meaning they can survive spawning events and return in subsequent years. However, that doesn’t mean they will survive. This is especially true of anadromous Dollies. The vast majority of fish are first-time spawners. A minority of individuals are second-time spawners. Rarely do anadromous Dolly Varden survive to spawn three or more times.

Eggs and Alevin in Redds

Char embryos require cold, clean, and oxygen-rich water for optimal development. Redds must also be free of fine sediment that could smother the eggs, and this is especially true for Dolly Varden.

The speed at which Dolly Varden eggs develop is temperature-dependent. Their embryos develop more rapidly at a given temperature than most other salmonids. Warmer conditions will lead to a more rapid progression of hatching as alevin and subsequent emergence as fry. However, it often takes six or seven months after fertilization before embryos develop into alevin and eventually emerge as fry.

Juvenile Dolly Varden in Streams: Fry and Parr

Dolly Varden fry typically emerge in late April and May.

Initially, fry often inhabit small pools and eddies along stream banks, which provide safety and abundant food. As they grow, they explore more extensively, inhabiting everything from tiny side channels to sloughs with still or moving water. Their habitats include gravel, muddy substrates, dense vegetation, large woody debris, and open water areas. Over time, larger pre-smolt Dollies tend to occupy riffles and smaller ones may be found in sloughs and isolated pools.

Springs and upwellings within streams are vital as overwintering sites during colder months. The warmer water provides a stable, ice-free environment that supports their survival through winter.

Diet of Juvenile Dolly Varden in Streams

Like most species of char and trout, Dolly Varden are opportunistic predators. The diet of fry and parr is largely influenced by their size. Initially, the tiny fry subsist on zooplankton, small aquatic insect larvae, and minute organic matter. As they grow, their diet diversifies to include larger aquatic insects, terrestrial insects, and other invertebrates such as worms and crustaceans. Dolly Varden also have an affinity for eating snails.

Where available, salmon eggs and fragments of salmon carcasses are significant food sources. Although larger Dolly Varden in streams may consume salmon fry, they are less predatory of young salmon than cutthroat trout and juvenile coho salmon.

Mature Stream-Resident and Lacustrine Dolly Varden

Dolly Varden are most well known as anadromous fish, but significant populations exist that lead entirely stream-resident or lacustrine lives. These Dollies generally don’t grow very large or live exceptionally long. Their diets are primarily insect-based, though they may also include population-specific items depending on their environment.

Stream-Resident Dollies

Stream-resident Dolly Varden are found in various forms across most populations. These fish spend their entire lives in the freshwater streams close to where they were born, rarely migrating to larger bodies of water. Many stream-resident populations are above waterfalls or velocity barriers. In Northern Dolly Varden populations, stream-resident fish are mostly male.

Many small stream-resident fish max out at around 6 inches (15.2 cm) and eight years of age. However, fluvial Dolly Varden in larger rivers grow somewhat larger and can live over ten years.

Lacustrine Dollies

Lacustrine populations are almost exclusively Southern Dolly Varden. This niche is typically inhabited by Arctic char in the Northern Dolly Varden’s range.

Lacustrine Dollies inhabit lakes and ponds and feed on a similar diet to their stream-resident counterparts. These lake-dwellers usually spawn in inlet or outlet streams, but a few populations spawn on lake beds.

Dolly Varden sharing lakes with cutthroat or rainbow trout are often subdominant. The trout dominate the littoral and near-surface habitat, while the char are more benthic.

Lacustrine Dollies rarely grow larger than 12 inches (30.5 cm) or live longer than ten years old. However, populations that share lakes with kokanee salmon can grow much larger. The kokanee fill the role of planktivores, and the Dolly Varden eat the kokanee.

Anadromy: Sea-Run Dolly Varden

Anadromy is a prevalent life history type among Dolly Varden in Northern and Southern forms. It’s almost exclusively used by Northern Dolly Varden. Typically, Dolly Varden migrate to the sea as smolts in the spring or summer after residing in freshwater for their first three or four years.

Once in the ocean, Dolly Varden feed through the summer before returning to freshwater to overwinter. Northern Dolly Varden typically seek rivers with spring inputs for overwintering, benefiting from the stable, warm water these habitats provide. In contrast, Southern Dolly Varden migrate to and overwinter in systems with large lakes. These lakes are often located in different watersheds than their natal streams. The Dollies will migrate into as many rivers as necessary until they find a suitable lake.

Most Dolly Varden ocean migrations are short (< 100 miles) and coastal-oriented. However, some populations undertake significant migrations. Dolly Varden from the Kivalina, Wulik, and Noatak Rivers of Alaska often migrate over 1000 miles (1609 km) to overwinter in the Anadry River in Russia.

Sea-run Dollies usually don’t spawn after their first summer at sea. Oftentimes, they only mature after their second summer. Spawning anadromous Dolly Varden are typically between 12-18 inches (30.5-45.7 cm) in length. Even though these char are iteroparous, anadromous Dollies don’t often survive spawning. The majority of fish are first-time spawners. A minority spawn for a second time. And less than 1% live to spawn three or more times.

Dolly Varden Predators

Dolly Varden face numerous predators across their life stages, from aquatic rivals to aerial hunters.

Juvenile Dolly Varden are preyed upon by many species of birds, including mergansers, cormorants, cranes, herons, and egrets. Piscivorous fish like cutthroat trout, coho salmon, and rainbow trout are also occasional predators of juvenile fish.

Juvenile and adult Dolly Varden are preyed on by pinnipeds like seals and sea lions. Osprey also prey on Dollies big and small, as do northern river otters.

Adult Dolly Varden must contend with larger threats in freshwater and the ocean. Brown bears often feed on them during spawning. Eagles like the bald eagle, Steller’s sea eagle, and white-tailed eagle opportunistically take Dollies. Beluga whales consume them in both the Arctic Ocean and the Pacific. Additionally, salmon sharks also likely prey on Dolly Varden.

Humans remain one of the biggest predators, harvesting them extensively across their range.

Dolly Varden Declines and Threats

Dolly Varden are a resilient species but face threats that have led to local population declines. They aren’t listed in the US under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). However, the northern form of Dolly Varden in Canada was designated as “Special Concern” under the federal Species at Risk Act in 2017, reflecting growing concerns about its future.

Overfishing has been a persistent threat. An extreme example is Alaska’s misguided Dolly Varden bounties from 1921-1939. Anglers received between 2 and 5 cents per tail of Dolly Varden turned in, as they were mistakenly believed to be highly predatory of salmon fry. Over 6 million tails were submitted. Over 20 thousand tails were examined in 1939, revealing the vast majority of captured fish were coho salmon, followed by rainbow trout, with Dolly Varden making up the remainder.

Dolly Varden often congregate in specific river and lake systems that offer suitable overwintering habitats. This behavior makes them particularly vulnerable to overfishing and habitat destruction at these critical sites.

Habitat modification remains a serious threat. Activities such as logging, road construction, and urbanization cause sedimentation and degradation of spawning and overwintering habitats.

Moreover, climate change presents a formidable challenge. The warming and drying trends threaten the cold, clean water and spring-fed systems essential for overwintering. Reduced groundwater flow and lower water levels may dramatically impact these critical habitats. This is compounded by other anthropogenic threats like offshore development, which can impede their migration routes.

These combined factors underscore the precarious situation of Dolly Varden, necessitating concerted conservation efforts to safeguard their future.

Dolly Varden: More than Just a Pretty Fish

Few fish have such a colorful history as Dolly Varden. Hopefully, this article has shed light on the intricate world of these misunderstood salmonids.

Dollies face challenges from overfishing, habitat destruction, and a warming climate. However, many of these challenges can be overcome. These beautiful char are highly adaptable, and with our help, they should continue to play their vital role in many ecosystems.

Thank you for taking the time to learn about Dolly Varden. Your interest and awareness are crucial first steps in conserving these remarkable fish.